A new new thing

Our reaction to a new thing is quite unpredictable. How will we react to this new environment?

We’ve probably heard a lot about inflation over the last few weeks. Like this tweet

Its no surprise to see Google search trends showing what we see here. The dreaded number is going up all around the world, way beyond the targets global central banks set for their respective countries. Energy, food and housing costs have crept up considerably which has started to become a real problem. I tried to imagine myself in an environment like this where living costs keep going up. What would I do? How am I and other people reacting?

I realised a lot of us have not seen this ever in our lifetime. You would probably have to go back to the 1980’s to see inflation prints hitting 7% in large economies of the world. For myself, and a lot of us, increasing prices and higher costs of living is a very new new thing.

At the same time you see how we live in the subscription economy where access to everything is so affordable. Open Spotify or Netflix and you can have millions of titles of content for a mere 10-15 euros a month. It takes me back to the days where you went to the music or DVD stores buying music, movies or games with a 15-20 (or maybe more) bucks. Per title. Today 12-15 bucks a month gives you easy access to millions of of that you can binge on forever anytime you want. What amazes me is the fact that how much we have got ourselves accustomed to this very affordable access. It is very much embedded in our lives now. Especially the younger generations, who are now growing up with it, know no other way of living.

How did we get this far?

The journey to low cost consumption

The last two decades saw constant improvements and innovations in tech which allowed software companies to massively drive down their marginal costs of production and disrupt legacy businesses (in turn driving down marginal costs of consumption for their customers). Globalisation played its part too. Flow of people, goods and ideas increased tremendously since 1990, with countries coming increasingly online and opening up their markets to the rest of the world. Both tech and globalisation, combined with increasing productivity, unleashed deflationary forces at full steam that drove down inflation and consequently, interest rates all over the world.

Low rates pushed investors and savers along the risk curve as well with ever abundant capital seeking higher yields and returns. A lot of it also got allocated to Venture, driving down their marginal cost of capital. This ever increasing capital spigot allowed these young companies to build, innovate and offer products and services at ever lower prices to attract customers and establish themselves, even at the cost of not making any money at all.

And here we are subscribing to everything we need in our lives for a few euros a month, partly subsidised by the VCs and mostly driven by the rest described above.

Here’s a chart of costs of select goods and services until the pre-Covid times. Assuming the U.S being representative of at least developed economies, a lot of them rose in-line with inflation (or declined significantly), except education and healthcare. Energy prices, being cyclical have had their share of causing a problem for periods of time but other living costs have largely been in check for a long-long time. Thanks to improving manufacturing processes, globalised supply chains and better technologies.

Shocks to the system

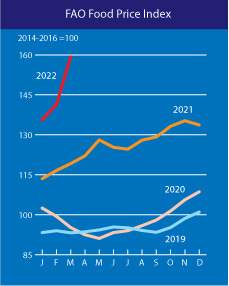

After a relatively calm period, the world was hit by two back to back shocks in quick succession, which has disturbed the ‘normal’ we all are used to. First it was Covid, which put a severe strain on the global supply chains and kicked off a supply driven inflation in goods. Then, the preposterous invasion of Ukraine was a major shock to the globalised system we all live in, driving energy (oil, gas and electricity) and food prices to levels not seen in decades (or ever). Global food prices are now at the highest levels seen since 1990.

For consumers, inflation starts to bite when things that have the largest weight in your spending start creeping up which leaves less for the discretionary items (like subscriptions, entertainment, leisure, travel etc.)

Considering that an average household spends 20-25% on food, 30% on housing and 10-15% on energy, a roughly 10% (or more) increase in each these categories starts putting a serious dent in the wallets.

Now that those Covid related savings are petering out (Americans built up an extra $4.2tn of savings during the pandemic with other regions having similar savings rates), how will we respond to this new new thing?

Finding real value in the subscription overload

Most consumers are likely to revisit what they are spending on and what they actually value more. The somewhat non-discretionary in this discretionary bucket. In the UK, people cancelled their streaming subscriptions in droves, with 1.5mn cancellations in 2022. Netflix shares plunged this week by more than a third after it lost subscribers for the first time on a quarterly basis in a decade.

As growth slows down in subscribers, price increase is a likely option for them to sustain the growth that is priced in their valuations. Two of the subscriptions I pay for already bumped up their prices this year. A precarious situation for companies right now, where they test how inelastic their products are to higher prices, in this environment.

Consumer confidence and retail sales have already begun showing signs of weakening in developed economies due to the impact of higher living costs. Could this cancellation trend spread elsewhere to other types of apps? Maybe, maybe not.

It seems like most people would not care to spend time to cancel a subscription to get back in later, especially if they were seeing their wages increasing in-line with their expenses. But human behavior is unpredictable, especially when we are facing with a new new thing (remember the first lockdown of 2020?)

A new market environment?

The environment might have changed for investors as well. After a stellar run for equity (both public and private), venture capital and bonds, the asset classes that won the last two decades are feeling the pain led by renewed volatility and investor outflows. Higher yields are pushing bond investors for the gates whereas long duration high growth stocks are being sold off for sectors gaining from higher inflation.

Bonds and equities have had a rough start to the year at the same time. Tech is getting hammered whereas value, energy and commodities, the biggest losers of the decades gone by are winning

The big money is seriously being taken out from past winners and reallocated to what is expected to work in this new environment.

Does institutional capital, that left fixed income and chased yield in private markets and equities, come back at 2-3% long-term yields? Does it give up its ESG principles (for a while) and comes back to energy/commodities seeking better risk-return profiles? The dispersion in outcomes is getting wider, and when that happens, a new environment forces new long-term winners to emerge in the markets.

Here’s a second order take: If rates go up taking cost of capital of businesses with them, and growth slows down, do large cap tech stocks start outperforming again? After all, these companies have a defensible market position and have the ability to pass on higher costs much better than smaller businesses. The valuations have slightly corrected too, maybe making them attractive again. We shall see.

Revisiting history books and the past is always helpful, but sometimes it something has to be experienced to be well understood. Reading about past pandemics was useful, but your pandemic playbook that you have with you now is your own. Inflationary environments of the past might produce some useful insights, but the one you live yourself will be the one that stays with you for the next time it comes around. For both how you respond in life and how you invest.

Until next time,

The Atomic Investor