How not to run a football club

A critical look from a financial POV at a football club that has a special place in my heart.

You would find me writing mostly about financial markets and investing, and at times about growth and noteworthy events in the world of business and finance. This one is slightly along different lines, and resonates with the world of football and finance. I jumped at this chance of writing about the sport, especially because this train of thought was mostly driven by Manchester United FC. The club has had a special place in my heart ever since I started following the beautiful game.

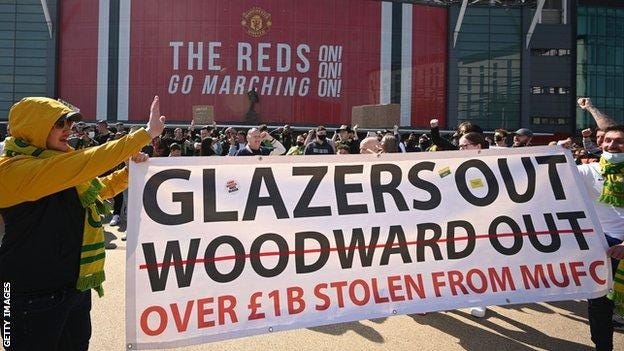

Following the shambolic state of events recently, and with the emotional duress it caused me and my fellow United fans, I wanted to take a step back and look at the club a bit more critically. The club’s troubles have been well known to its fans and to people who follow the game closely. It has faltered badly on the footballing side, failing to win the Premier League in more than a decade. But its commercial juggernaut has rolled on from strength to strength over that period, allowing the club to still be one of the biggest in the world by value. This disconnect between its core activity, the performance on the pitch, and its commercial growth has left the club in complete disarray.

The sorry state we see it in today and the problems it has been dealing with for years are deeply rooted in the decisions the management has taken off the field. Football is not an easy business to own and run by any means. The owners and the board can constantly find themselves walking this fine line between football and making money. The evolution of sport into a global, commercialised entertainment business meant that club owners could expand the commercial side of the business with broadcasting, merchandising, sponsors and marketing. United saw considerable commercial success, but a lot of came at the expense of decisions and investments needed to ensure long-term footballing success.

The club’s history off the pitch is riddled with sporting and business lessons. The more pages you turn to the past, the more you realise that this is How not to run a football club.

First, a bit of a background.

The start of Glazernomics

The story goes back to 2003 when Malcolm Glazer, an American businessman and the owner of Tampa Bay Bucaneers (Superbowl winners in 2021), started buying Manchester United’s shares (United went public in 1991 in London to raise money for stadium expansion). They ended up with 2.9% stake for GBP9mn, which was subsequently bumped up to 15% at the end of the year. The Glazer family was handed another 28.7% by the then owners (Magnier and McManus) due to an acrimonious dispute with Sir Alex Ferguson that dragged on for years (more on that here, and its completely unrelated to football). In 2005, they reached majority ownership and started buying out other minority shareholders, ultimately buying out the club for a total of GBP790mn.

Its normal for business ownership, including that of football, to change hands. But its an imperative for the current stakeholders to understand what it means for the future of the organisation. At that time, one had ought to look at why the Glazers wanted to buy the historic club, what was their strategy and if their interests were aligned with the long-term success of the club.

It was a textbook hostile-leveraged buyout. The Glazers bought the club with just GBP230mn of equity and loaded the club more than GBP600mn of debt right from the get go. United had zero debt in the past, and most of the growth capital before the Glazers came along was used to build the stadium, training facilities and the team. But 2006 was the start of Glazernomics, an era that was defined by underinvestment in the core assets of the business, loading up on debt (that till today restricts the club to invest more), paying the owners out handsomely each year, and setting the club up for failure in the future. It was probably one man’s genius, (Sir Alex) who had built a team and a culture that led them to the glories, that the inevitable was pushed forward for a few years.

Cashing out and reining in control

After six years at the helm with numerous episodes of backlash and fan protests, the Glazers decided to take United public one again. It was a major liquidity event as they offered 16.6 million Class A shares and ended up raising USD233mn. They cashed out handsomely by taking half of these proceeds home (roughly USD115mn) and leaving the other half for the club. In the prospectus filed at the SEC, they highlighted the use of IPO proceeds as to pay down the debt (in the image below):

Additionally, this created a dual-class share structure at the club where the Class A shares (the ones offered in the IPO) only had one-tenth of the voting power as Class B shares (which they already controlled more than 70% of).

The IPO brought a host of benefits to the club as well, but the Glazers cashed themselves out and further tightened the grip on any decision making at the board level. Quite inevitable when the owners are just here for filling up their coffers.

Plenty has happened since the advent of Glazernomics as the club has seen many periods of peaks and troughs (mostly troughs, to be honest). I tried zooming in mostly on the financial side of things and how the club is run (the footballing side was equally unacceptable). Misallocation of capital, which a lot of the club’s problems can be tracked down to, stood out most glaringly for me.

Stewards of misallocated capital

Capital allocation decisions are critical for long-term success and value creation. These decisions can be branched down to four-five choices that a steward of capital could have at any point: Reinvest in the business, pay down your debt, buy back stock or pay a dividend. In United’s case, capital allocation was a shambles any way you look at it.

Flailing reinvestment plans

Since the Glazers took over, reinvestments in the core assets, i.e the team, fell substantially on a relative basis. United's cumulative spend on players was below GBP200mn from 2005/06 - 2012/13 (The post Glazer Ferguson era), much lower than their noisy neighbours Manchester City and rivals Chelsea who spent GBP517mn and GBP384mn respectively. Very different approaches by new ownerships, those of City’s and Chelsea’s and that of Glazers. We can clearly see which one worked best in the long run.

Spending huge sums of cash doesn’t guarantee success (more on that later), but when your biggest rivals are outspending you and building the club from inside-out, you better keep up and build too, especially in a competitive market such as that of football.

If one wonders about reinvestments in stadiums or facilities, things don’t look good there either. United's last stadium capacity expansion took place in 2006, which the Glazers were obliged to complete as a part of the takeover. Clubs like Tottenham and City have spent hundreds of millions on building world class facilities and stadiums, whereas United’s were recently reported to be in a shambolic state. Its embarrassing that even Brighton and Leicester have spent more since 2011.

The debt overhang

One of the reasons that allegedly prevented the Glazers from reinvesting into the team was the ridiculous amounts of debt loaded on United’s balance sheet. After taking over the club, the new owners piled on more than GBP600mn of debt as part of the leveraged buyout. Debt is not detrimental to the business if you know how to optimise your capital structure and pay it off, i.e generating more free cash flow in the future for the business.

The Glazers did neither. The club’s cash flows were only used to pay off a tiny amount (right before going public) after which the levels started climbing again. They paid back a portion of it using the IPO proceeds in 2012, but it was refinanced it multiple times over the course of the ownership. What is even worse is that United has had to make over GBP850mn in interest payments alone till date.

Even though the cash on the balance sheet and free cash flow kept creeping up, the Glazers showed this astonishing contentment with keeping the club leveraged, and even took on more debt during the period.

From not spending to spending recklessly

The transition from one of the longest serving and most successful football managers in the history of English football to the next in line was always going to be a testing one. The Glazers pushed the club into the new era with an ageing squad and no planning. They embarked on this journey with an eye on the commercial growth of the business and appointed a CEO (Ed Woodward) with no footballing experience to lead it through these times.

“If I answer that just very simply and candidly, playing performance doesn’t really have a meaningful impact on what we can do on the commercial side of the business.”

Ed Woodward - in a TV interview in 2018

The transfer strategy during this period turned from an ideally planned and prepared strategy into a reactive one. United went on to spend almost EUR950mn on players (after player sales) from 2013/14 - 2021/22, matched only by Manchester City, which spent EUR970mn net. They signed a bunch of overpriced star players based mostly on their large social media followings and the ability to break shirt sale records.

It completely changed the fabric of the squad. Players would come to United not with the hunger and mentality to win but to rake in those millions. United had the most inflated wage budget in the league when you compare it with the performances and titles on the pitch.

On the footballing side, they could have had financial success with player transfers by having the right people in charge. We’ve seen clubs like Ajax in the Netherlands, Borussia Dortmund in Germany and Benfica in Portugal buying and nurturing players on the cheap and selling them on to big clubs for 2-3x their purchase price. United did the exact opposite of that - Buying high and selling low.

It was reckless, it was unplanned and it was being led by an inept team with no footballing experience. It didn’t matter to the owners as long as United were attracting sponsorship deals and seeing merchandise sales go up. They would argue they spent the money, but they wouldn’t want to discuss the appalling record of the return on this invested capital, which you would be measuring in footballing terms in titles, points and goals. It has all trended in one direction only - south. If you do it the right way it looks something like this:

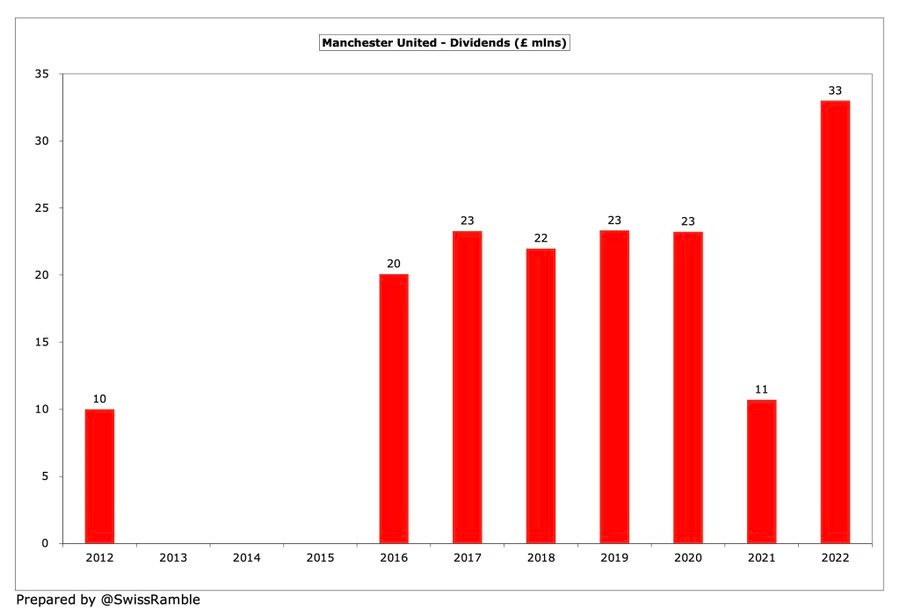

More juice for themselves

After a strong run up in revenues, the Glazers started paying a dividend in 2016 of roughly GBP25-26mn a year, roughly 10% of the operating cash flows back then. It was more juice for themselves, and a bizarre capital allocation decision, especially when reinvesting it back in could have been meaningful for the club’s operations. They’ve taken out almost GBP120-130mn in dividends since then, and not surprisingly plan to continue paying it…to themselves.

While there’s probably more shortcomings at United at the footballing level, the management’s capital allocation record and the state of the club’s finances is strong evidence of how football and finance are joint at the hip today. You need experienced directors who are technically sound and are adept enough to run the footballing side of things, in which United have failed miserably.

The club's board and CEO might believe they can run a separate commercial organisation regardless of their investments on the footballing side, but its the football that ultimately drives value creation in the long term both for fans and the other stakeholders. Not the other way around. But what would they know?

Until next time,

The Atomic Investor