The AI Capex debate

Tech and finance have been dominated by the AI bubble talk for far too long now. Here is my take on it using some computations, frameworks and theories.

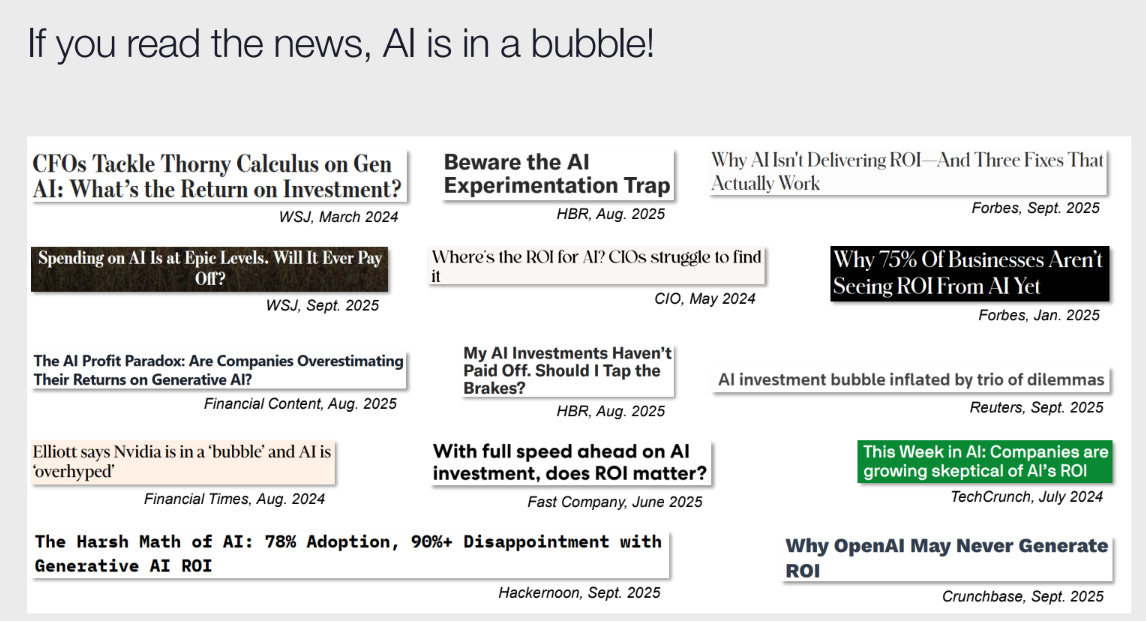

If there was an award for the most used and misused word of the year, the word ‘bubble’ would be an undisputed winner for years in a row.

We are now 3 years into current technology cycle and every quarter post earnings we get a sentiment check on where we are on the exuberance - pessimism spectrum. The durability of the momentum that has been powering the upwards move in the markets gets questioned time and time again.

We have had several ongoing debates since the start of the cycle - AI adoption, margins, scaling laws, valuations, and now the eternal AI capex bubble or not a bubble debate.

Even one of my favourite investors and thinkers, Josh Wolfe of Lux Capital, put out a tweet recently on the lack of value or returns on Big Tech capex.

I felt a simple statement or a back of the envelope calculation like this needed a deeper analysis. I understand the counter-argument: all this investment is billions of dollars of capex on fast depreciating infrastructure and high obsoletion risk, based on demand that is still yet to reach its peak and the technology yet to reach full maturity.

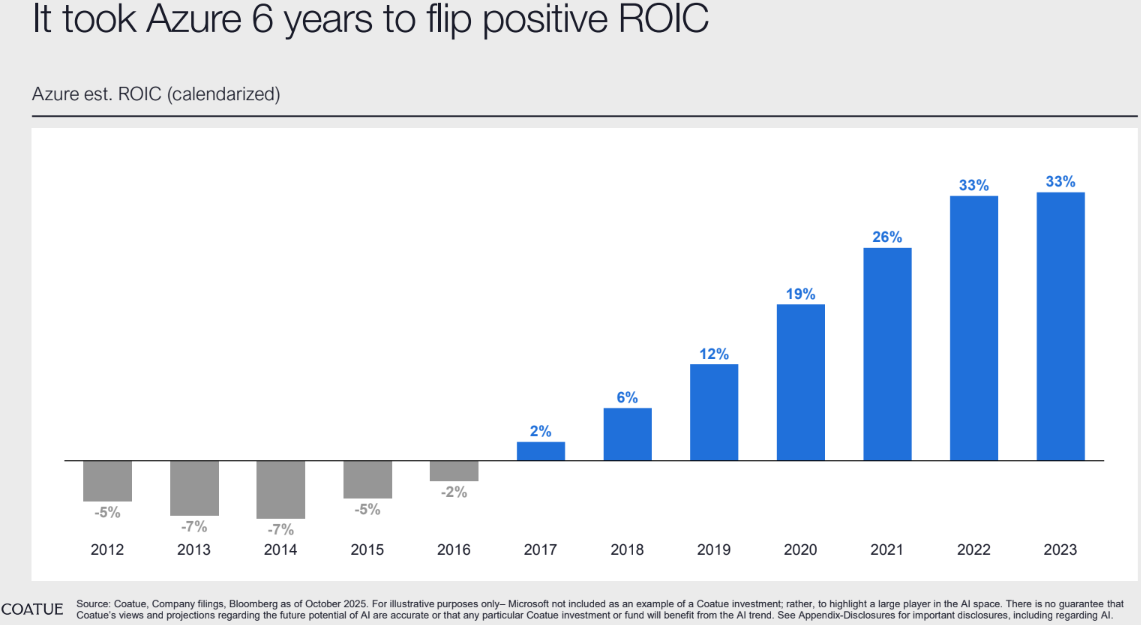

But here is how I see: it is missing the forest for the trees. The investment is predominantly long term in nature, not for returns from one quarter or one year to the next. We might not remember it now, but it took Microsoft several years to get to positive ROIC territory for Azure.

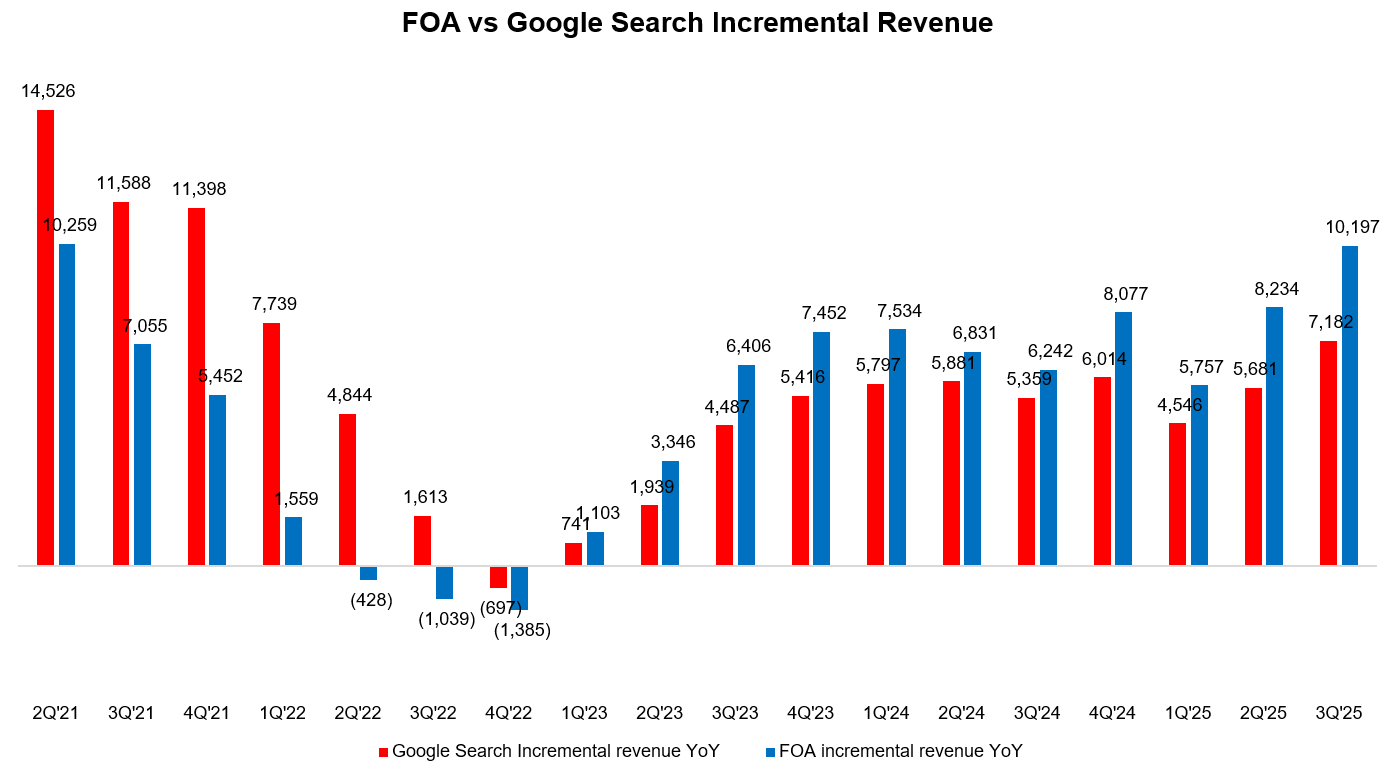

Second, all the investments in AI is not just allowing the Mag 7 to enter new product markets (see Google if you do not agree), but it is significantly improving their existing core business and deepening their moats.

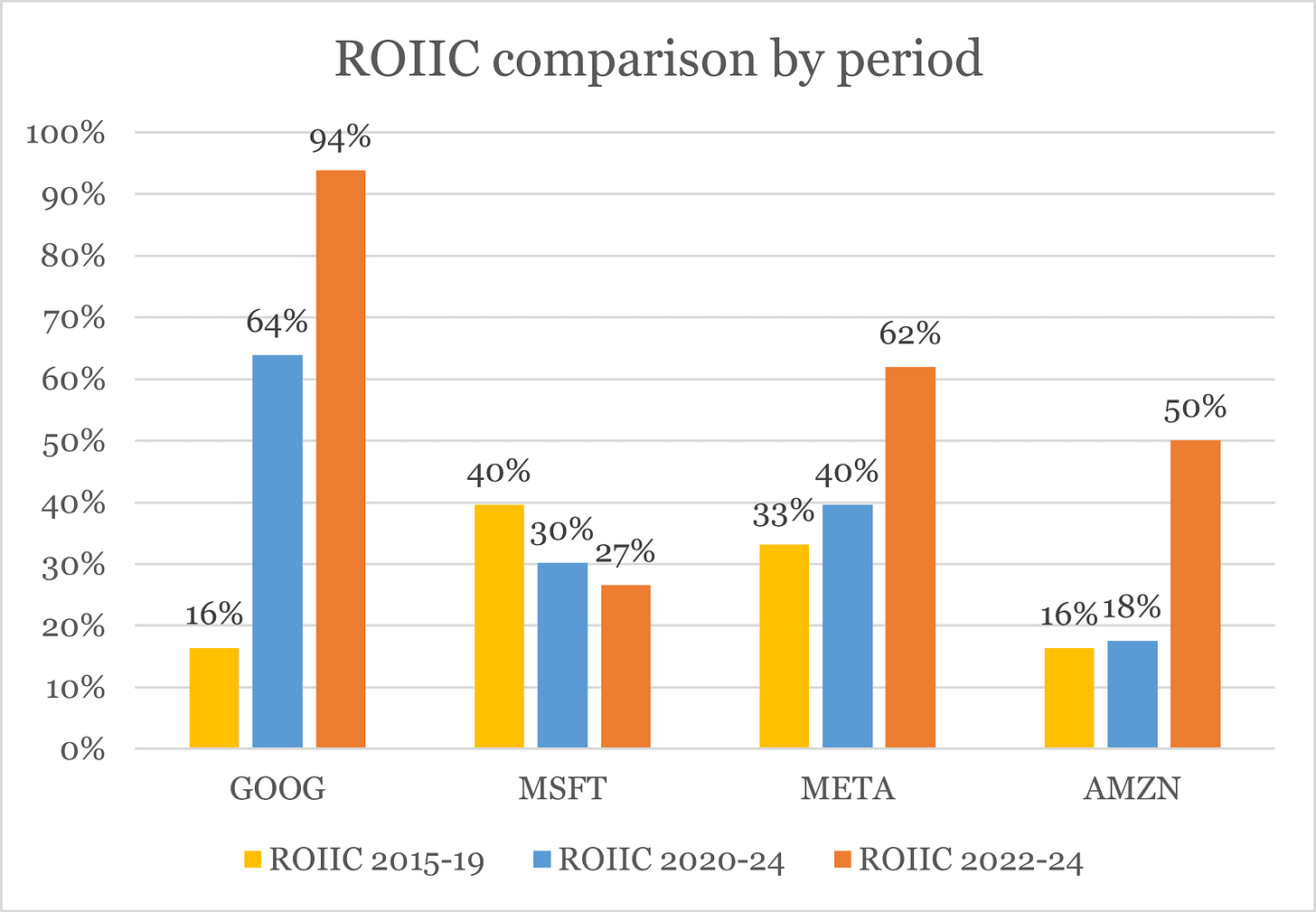

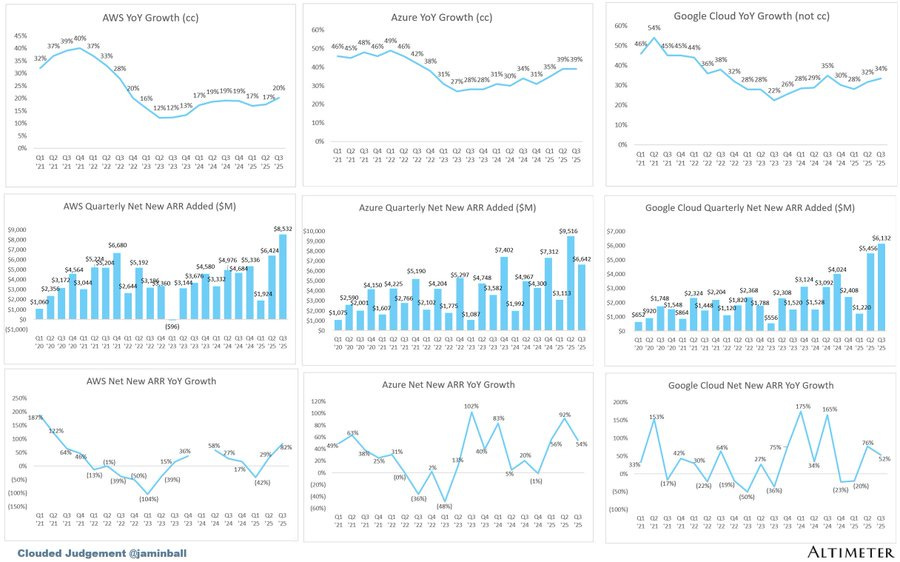

I computed the Return on Incremental Capital Invested (ROIIC) for these companies and compared them over different periods as a test for increasing marginal returns on capex (whether incremental ROIC improved as AI investment ramped). I was not surprised (more on that below).

I agree it might be a bit of AI capex FOMO for Big tech, but it is now existential for them, not optional.

And like many other moves in the market, this cycle could turn out to be reflexive as well.

So what is really making people so jittery?

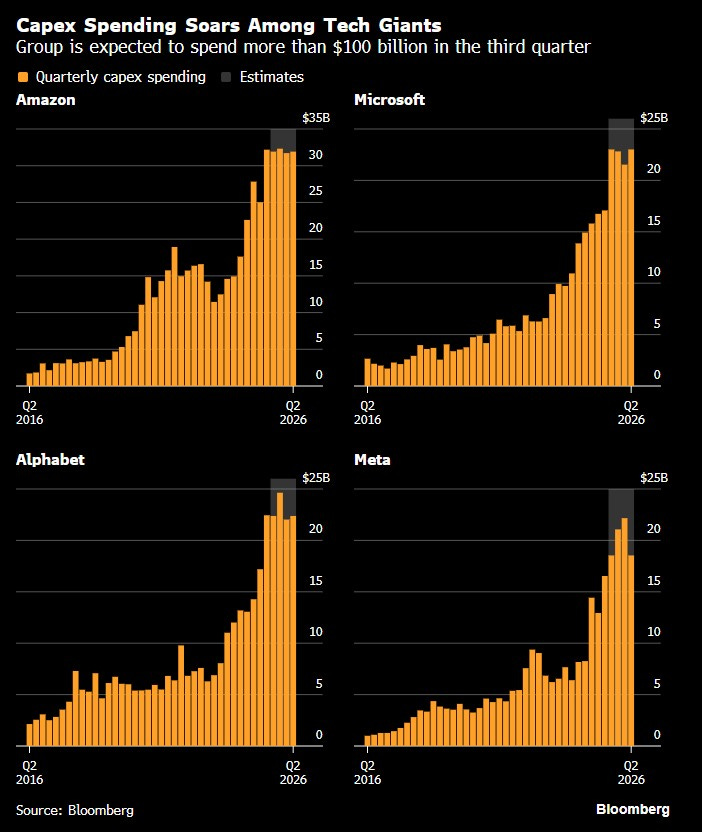

The shear scale of the investment in this short a period rhymes with a painful boom-bust event

We, for better or worse, are pretty good at pattern recognition. The absolute dollar amount of billions of AI related capex just over the past 3 years is taking us back to the dotcom bubble where billions were ploughed in to build the infrastructure layer of internet cycle (the fibre networks).

A fear of the ghost of depreciation eating into the earnings of these stocks continues to creep in. Some well known short sellers, who have now shut shop and are now hiding behind a paywall, are accusing the largest companies in the world (by market cap) of inflating the earnings by extending the useful life of the AI equipment (which lowers the annual depreciation). So much for pattern recognition and literally painting them as the “Enrons of the tech bubble”.

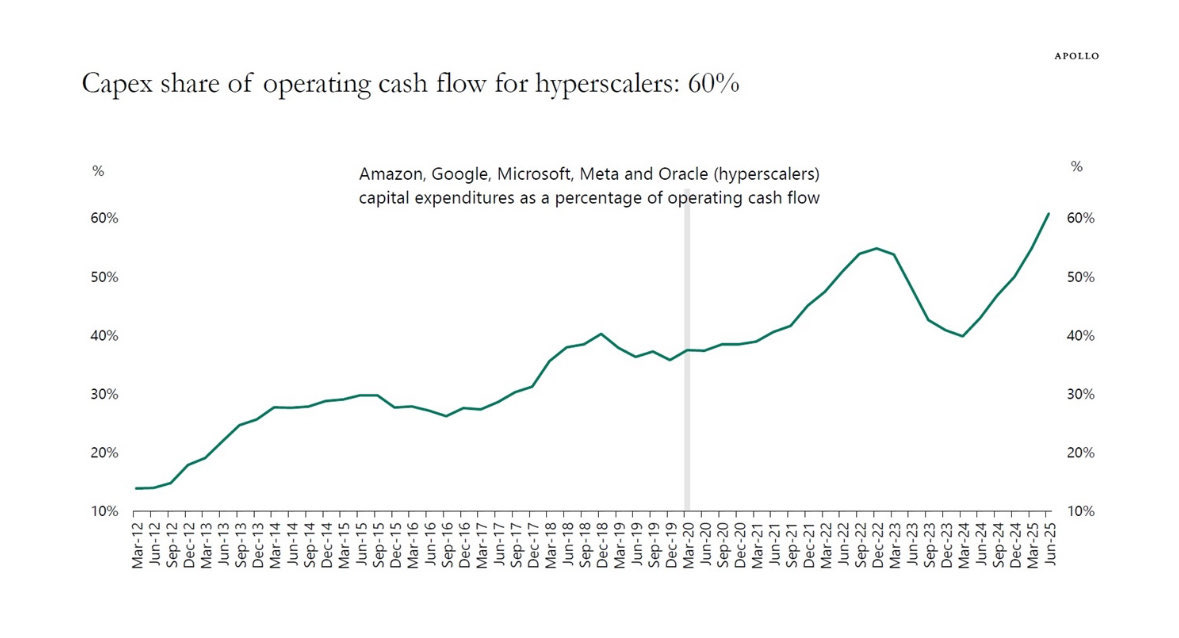

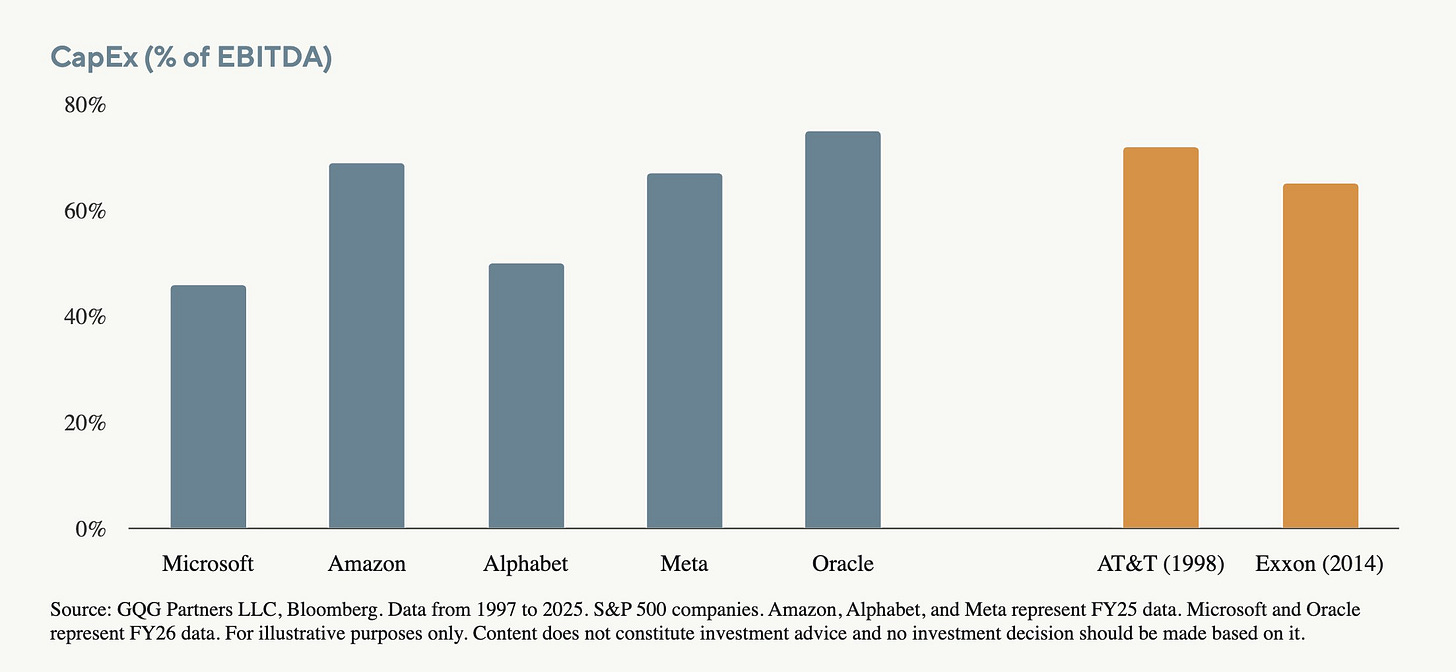

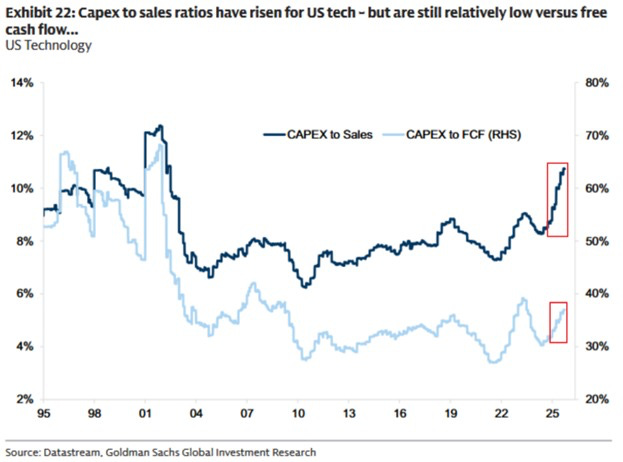

What is typically left out of the conversation is the difference between how the capex is being funded now vs the cycles they are compared to - a mix of growing base of cash flows and debt. Notice where the capex to FCF was during the actual bubble this cycle is compared to.

A levered bet is what exposes you against a slowdown or a downturn as opposed to a free cash flow funded one. Where deployment timing and amounts can be adjusted based upon where you are in the cycle, as compared to creditors knocking on your door if it does not work out as expected in a debt only funded investment cycle.

But where are the returns on all this investment????

Even if you are funding the capex mostly via cash flows, there is an opportunity cost of all these dollars being deployed. Which is where the returns argument comes in (as Josh Wolfe argued in his tweet).

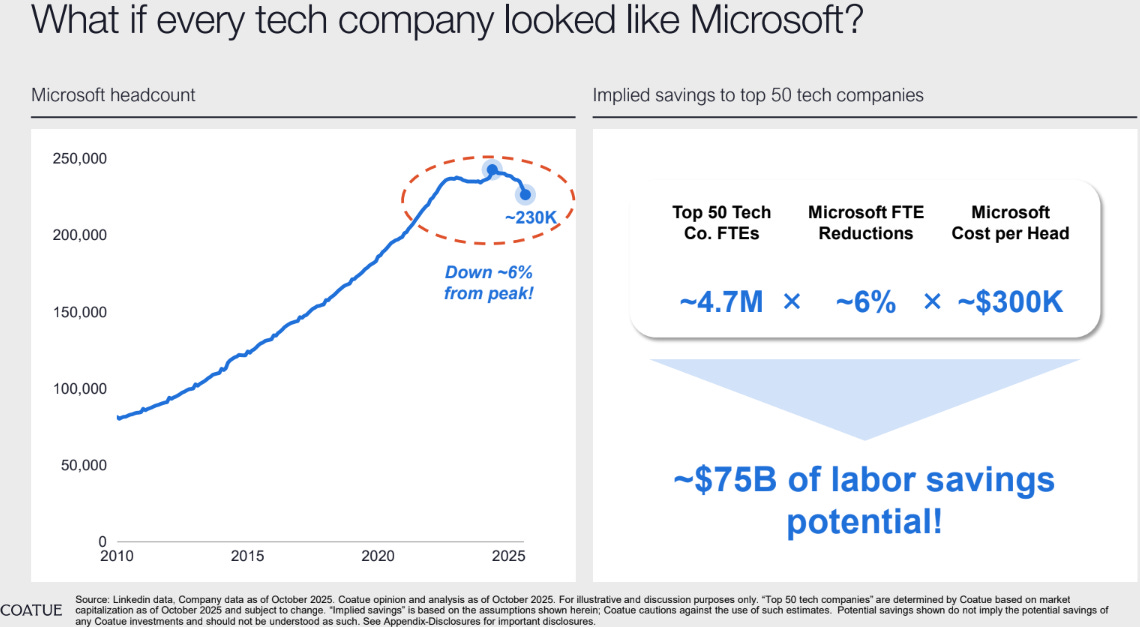

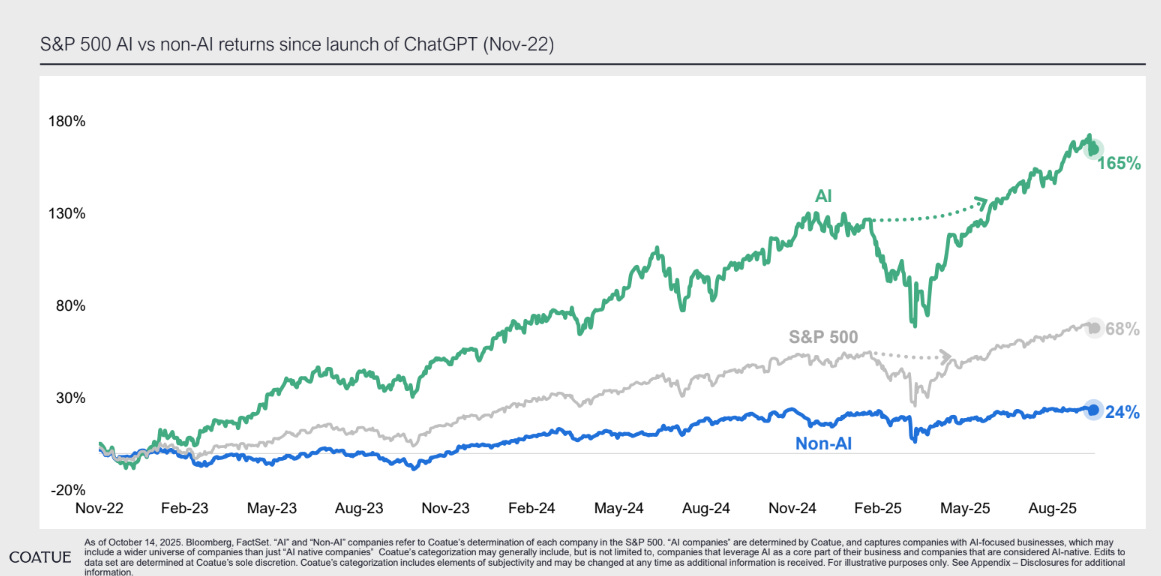

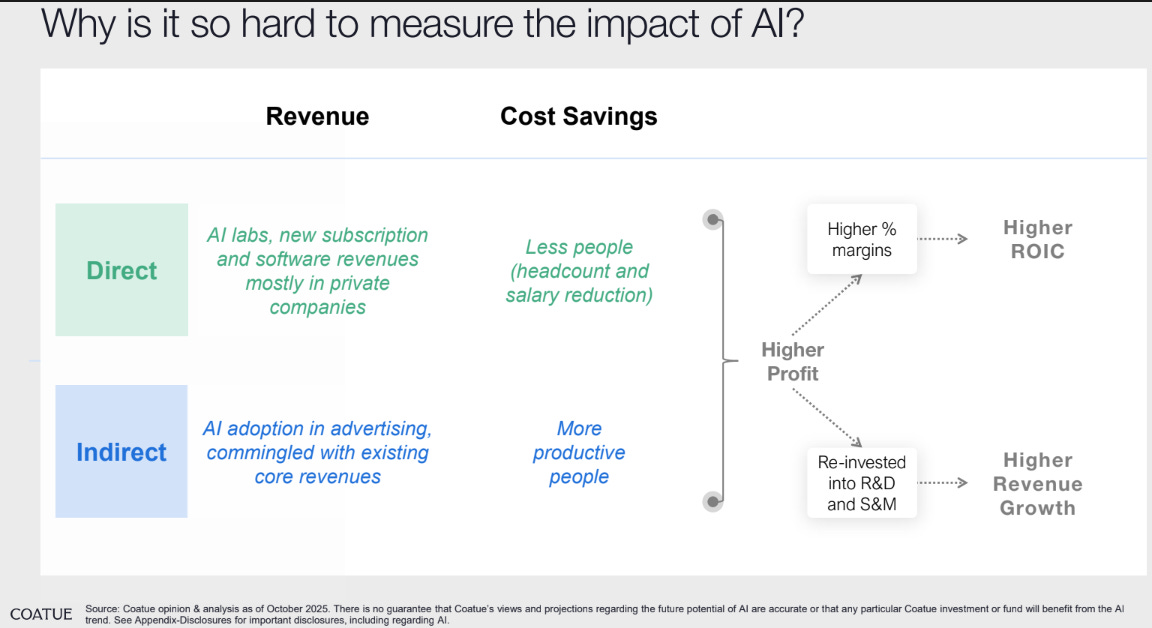

I tried using this simple framework published by Coatue to measure the impact of AI on the top and bottom line, and the ROIC (using cumulative ROIIC).

Since investment cycles in tech are generally long term, it made sense to compute the cumulative ROIIC over periods - 2015-19 (pre - AI buildout) vs 2020-24 (AI buildout). 2022-24 was also computed to normalize for the Covid-19 period.

**Not normalized for GAAP non-cash charges and R&D capitalization effects (AI R&D is expensed immediately but is long term in nature) which understates the operating income (NOPAT)

There seems to be clear increase in the marginal returns on investment over periods for all but Microsoft. If you use ROIC as an indicator for long term economic value added for a business (above the cost of capital of course), this chart should put a smile on your face as a shareholder. Increasing returns to scale is what dreams are made of.

The operating income is essentially driven by both top and bottom line impacts.

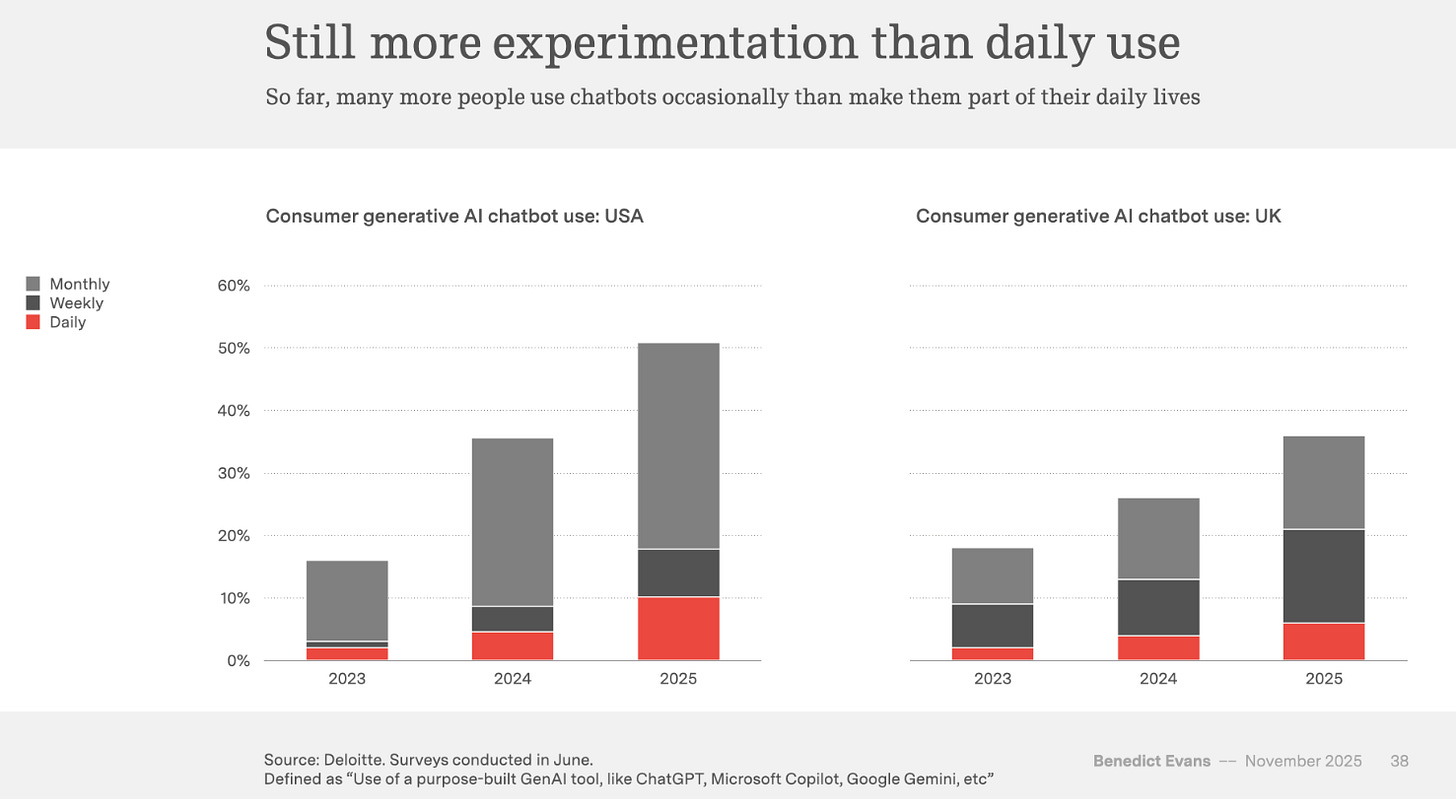

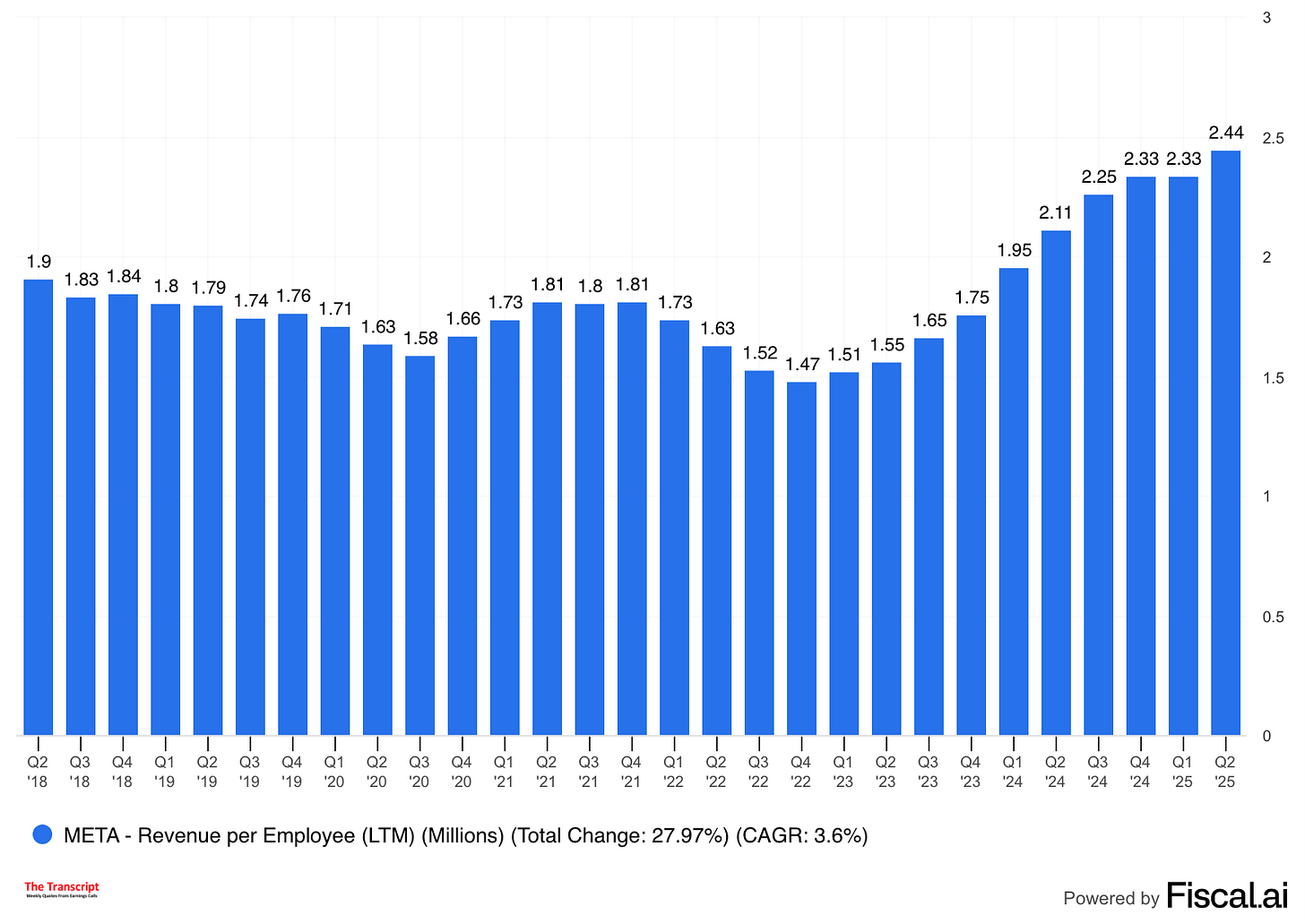

For the top line, one can look at revenue growth rates, product usage, number of active users etc. as a test of the invested capital directly improving their core business, which at that scale is even more valuable.

Cloud:

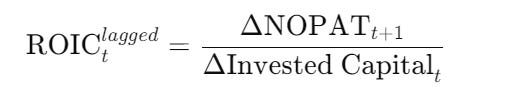

All three major hyperscalers (AWS, Azure, Google Cloud) revenue growth rates have reaccelerated substantially since 2023, a direct result of new models and AI related services that they have been introducing.

Ads:

Search (GOOG) was +14.5% in Q3 25, Youtube ads +15%, Meta overall ad growth was +26% with both impressions and ad price growth reaccelerating. AMZN ads was +22% in Q3 25.

Engagement:

Across Facebook, Instagram and Threads, our AI recommendation systems are delivering higher quality and more relevant content, which led to 5% more time spent on Facebook in Q3 and 10% on Threads. Video is a particular bright spot with video time spent on Instagram up more than 30% since last year. And as video continues to grow across our apps, Reels now has an annual run rate of over $50 billion. - META Q3 2025 earnings

Rufus, our AI-powered shopping assistant has had 250 million active customers this year with monthly users up 140% year-over-year, interactions up 210% year-over-year and customers using Rufus during a shopping trip being 60% more likely to complete a purchase. Rufus is on track to deliver over $10 billion in incremental annualized sales. - AMZN Q3 2025 earnings

Enterprise:

MSFT’s Productivity and Business Processes segment up 17% in Q3 25, driven by Copilot, automations and AI assistants led increase in usage.

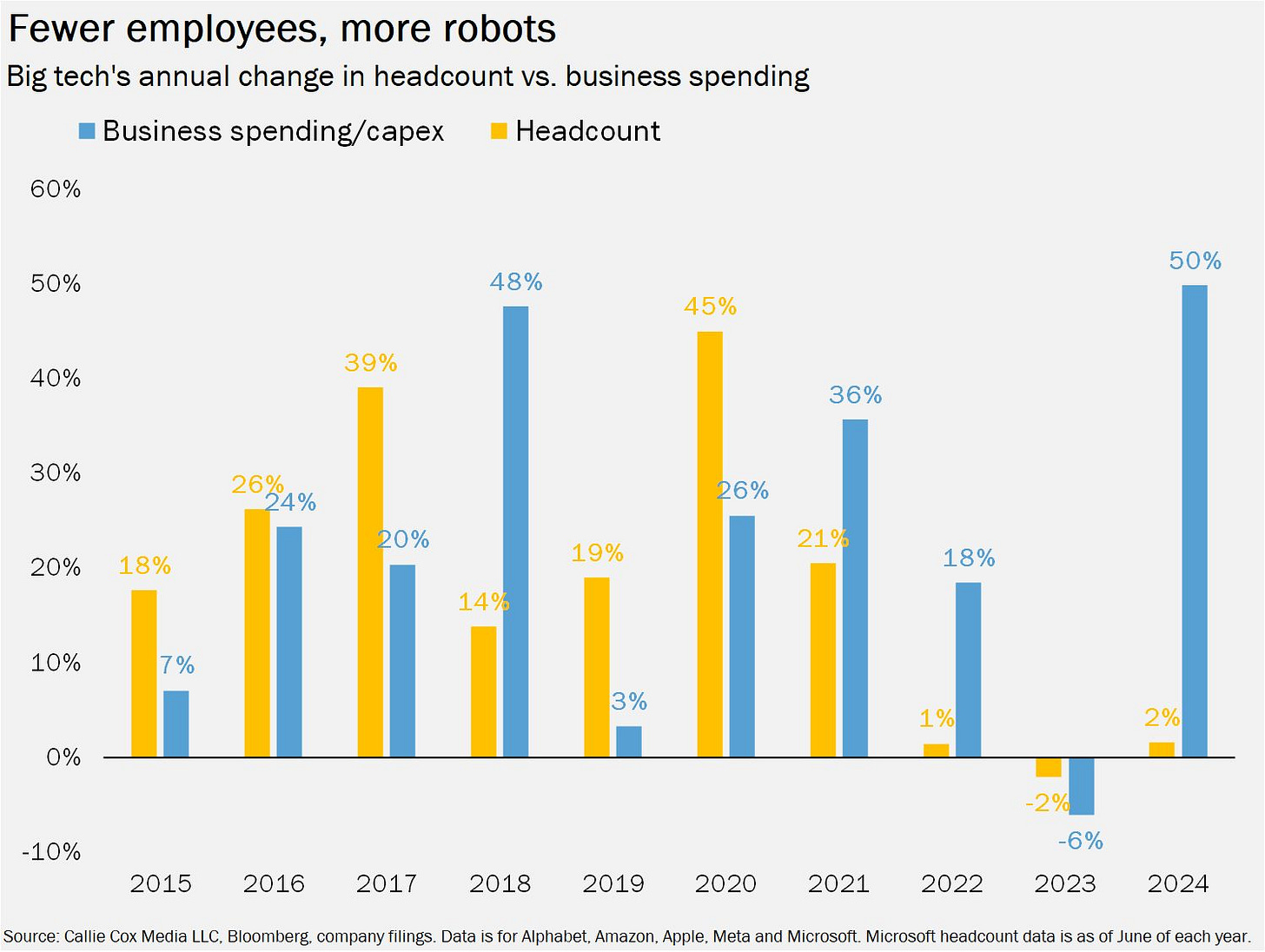

Bottom-line impacts are related to cost efficiencies, which we have started to notice with headcount growth. Sadly, they also have long term implications for our society and the labour market.

Reflexivity rules

Using George Soros’s theory of reflexivity to analyse the cycle makes it even more interesting.

The core concept of the theory posits that the markets simply do not move towards equilibrium just based on fundamentals (prices where buyers and sellers agree at a point in time). Instead it operates through a two way feedback loop with two key components:

Fallibility: Investors have imperfect understanding of reality, heavily influenced by cognitive biases and emotions, leading to systematic mistakes in assessing fundamentals.

The Reflexive Loop: Rather than fundamentals driving stock prices, stock prices actually drive fundamentals. What investors think about reality influences reality itself, which then shapes their thinking again.

Applying this framework to the current cycle, one can look at periods of rising Mag 7 or Big tech stock prices (since 2023) where investor enthusiasm around AI drove prices up along with some early results in the fundamentals which justified increasing capital spending.

But now as some of these stocks enter considerable drawdowns from their recent highs as the markets start to question the spending (Meta for example, which has corrected 25% from its highs), the reflexive loop is likely to act in reverse where falling stock prices make Big Tech readjust the amounts and timing of the capital spending, self correcting the speculative elements of the AI capex and forcing upon some capital spending discipline on them.

Meta is a case in point. It was reported last week that there could be potential budget cuts of as high as 30% in the Metaverse segment in 2026, a direct response to stock price correction. AI spending will still increase, but instead of putting in more of its cash flows on AI a part of Metaverse related spending will be reallocated towards higher priority AI related projects.

Why? you may ask.

Because stock prices matter to the managements. In the current AI buildout phase which is getting ultra competitive by the minute, stocks are the currency used to attract talent and make acquisitions, the value of which depreciates as the prices go lower.

A lower stock price makes the value of equity packages less attractive and puts you at a competitive disadvantage in recruiting top AI talent. Then, stock based acquisitions become more dilutive and less attractive to the targets at a lower price.

This self correcting mechanism might as well take care of some of the frothiness we might be witnessing in this AI cycle.

So which way are we leaning in this debate? You can probably infer where I stand from my takes above.

Until next time,

The Atomic Investor

Good read!

Very well quoted