The other side of the AI equation

It was an eventful week in tech and AI. While AI optimists are watching the demand side to do its magic, a lot hinges on the other side of the AI equation.

There are years when nothing happens and then there are days when decades happen. This last week had some of these kind of days where it felt like a whole decade had passed.

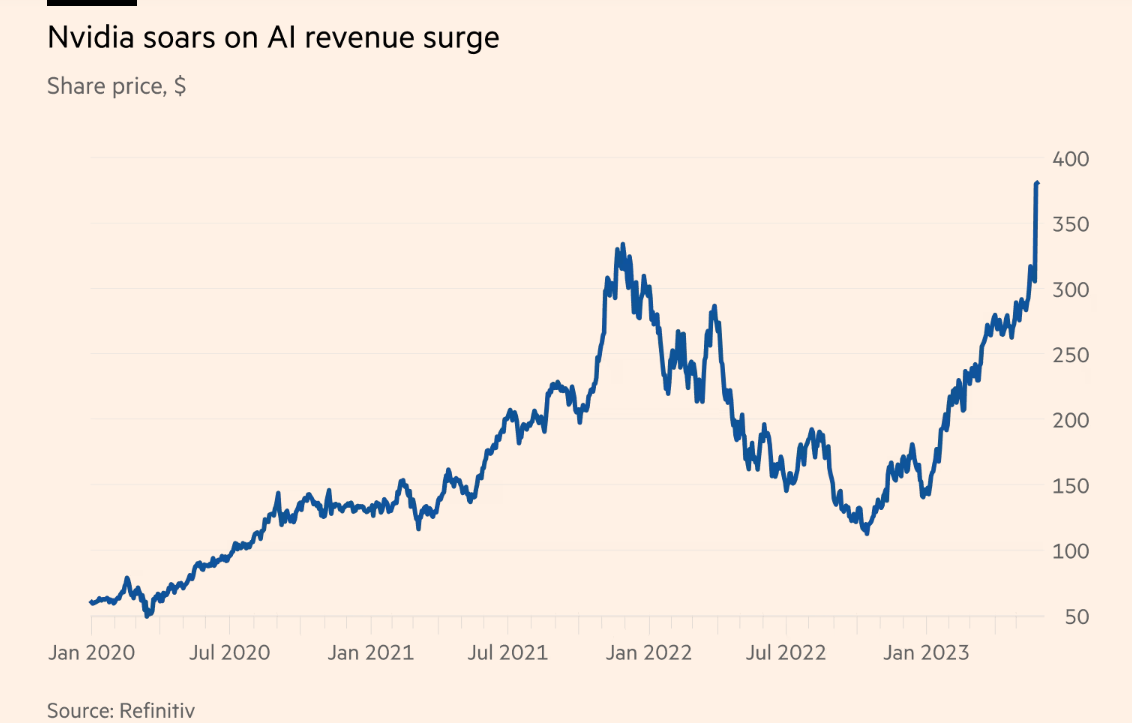

This week, Nvidia released its astonishingly good Q1 results confirming that demand for AI was red hot. It projected its next quarter revenues to be $5bn more than what was the consensus before, driven by its H100 and A100 chips used in data centres for AI related compute. The market reacted frenetically as the stock price soared, adding almost $200bn in market cap for the company in one day. It also entered the coveted $1tn market cap club the same week. For context, the stock had added roughly $180bn in market cap in the whole of last decade!

But not just that. This week drove the AI cycle into full gear (if it was not in it already) and pushed the markets into a frenzy where it almost felt like many closely held beliefs and expectations in AI were turning into reality. Tech cycles usually move in decades, but it seemed like the past couple of weeks literally pulled forward a lot of that progress.

In tech cycles of the past, the demand side of the equation has captured almost all the value. The Internet, mobile, Cloud/software cycles all saw value creation and capture by companies building products and platforms powered by these technologies. The supply side mattered less as the incremental cost to produce and distribute the products and services decreased massively, creating a ton of value to be captured by the tech companies serving the demand.

In this cycle, the market seems to have picked its first winner. This time around though it is from the supply side. Nvidia, the AI chip supplier seems to be the only arms dealer in this AI war. Maybe this is the order in which winners are always created. In a market where supply is concentrated, the suppliers capture most of the value until a groundbreaking product or platform for the technology emerges on the demand side. ChatGPT is one of them, but it is still only a first version of one of the use cases of AI or gen AI.

However, I’m not so sure this tech cycle is playing out like the ones before.

Less room to build moats

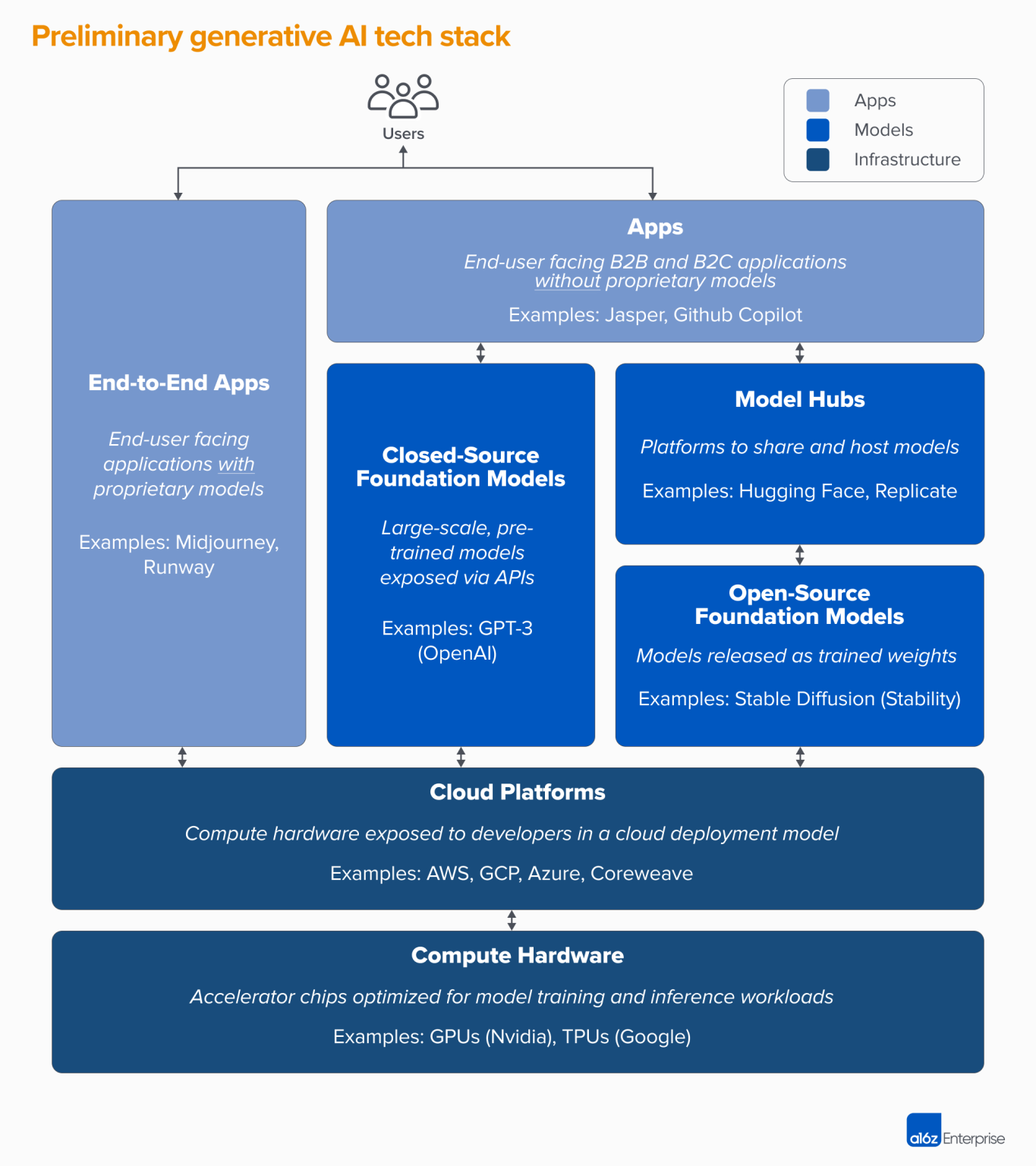

To put things in context, here is a map of the AI stack and value chain by the perpetually bullish folks at 16z.

Given the current state of AI, there seems to be little room to capture value if you’re anywhere above the infrastructure layer. Getting started is turning out to be pretty hard as the supply for AI chips for model training is highly constrained.

“It’s happening at hyper scale, with some big customers looking for tens of thousands of GPUs.” - Head of Nvidia’s Hyperscale and high performance computing business

So much so that success for many companies building in AI would depend on whether they can get their hands on the hardware needed in the first place. Cloud platforms are the largest players in big tech able to source this in bulk for their data centre workloads, and have, in addition, their own teams of engineers working on proprietary chips to complement their AI products and platforms. This puts them in a position to build and iterate much faster in the space.

Then, companies working on embedding AI into their products or building AI products altogether are going to have an awfully hard time differentiating themselves. Open source models are already out there in abundance, along with other proprietary models which you can access via APIs, which makes it unlikely for a business to differentiate itself in the model layer.

One way to have a defensible business model could be to train and retrain your own model and make it better, but that could end up needing sizable compute resources time and time again, which is a cash incinerator in itself.

Less differentiation eventually leads to companies competing on pricing, which then leads to margin compression and them generating little cash and making no money. Would this be viable in an environment where cost of capital is much much higher than what we had in the last decade?

Incremental cost to produce are enormous

Unlike previous cycles where incremental costs to serve one additional customer or ship one more product were minimal or low, this one has a much higher input costs which AI optimists are not paying much attention to. If you’re going the ‘buy your own infrastructure and train your model’ route, each H100 Nvidia chip would cost you about $40,000. Those hardware costs can easily balloon once you scale and build much larger models.

If you’re going the ‘pre-trained model’ or ‘hosted AI infrastructure’ route, you lose some of the control you might have with the former route, and in addition, would be spending most of your budget on compute costs. Elon Musk was pretty open about the sky high compute costs at a conference recently stating that “The cost of compute has gotten astronomical” and that “the minimum ante for gen AI server hardware is around $250mn”.

The hope is for compute and training costs to keep falling as chips and the software it runs get more efficient, which has always happened with previous cycles and technologies. ARK Invest put out a research piece last November stating that training costs have decreased at a rate of 48% per year as performance has increased 195x overall since 2014. We’d need that to continue if we want other areas of the AI stack to accrue more value per $ spent.

Which path could AI follow from this chart here? (From Janelle Teng on Substack)

Infra suppliers are extremely well positioned to capture most of the value

Infrastructure suppliers, both chip makers and Cloud platforms are touching everything flowing through the value chain. Chips are quickly becoming the lifeblood of AI as the demand expands much faster than the supply. Cloud infrastructure providers like AWS, Azure and Google Cloud have the scale and data centre capacity needed to provide compute to a large proportion of the industry. They also spend almost a $100bn in capex a year to build and expand capacity and have their own chips to control the efficiency and performance, and also reduce dependency on other suppliers.

According to 16z,

“A lot of the money in the generative AI market ultimately flows through to infrastructure companies. To put some very rough numbers around it: We estimate that, on average, app companies spend around 20-40% of revenue on inference and per-customer fine-tuning. This is typically paid either directly to cloud providers for compute instances or to third-party model providers — who, in turn, spend about half their revenue on cloud infrastructure. So, it’s reasonable to guess that 10-20% of total revenue in generative AI today goes to cloud providers.

On top of this, startups training their own models have raised billions of dollars in venture capital — the majority of which (up to 80-90% in early rounds) is typically also spent with the cloud providers. Many public tech companies spend hundreds of millions per year on model training, either with external cloud providers or directly with hardware manufacturers.”

No wonder companies like Anthropic, OpenAI, Stability AI and others are partnering with the big 3 Cloud providers to corner some of that compute for their products. This is allowing the Big 3 Cloud providers to grow alongside the fastest growing AI companies, giving them an opportunity to capture additional upside like Google and Microsoft did by taking an equity stake in these companies.

All of this makes them extremely well positioned to capture most of the value being created in AI.

The other side of the AI equation i.e the costs and the inputs related to the supply side are turning out to be much more important than what we’ve seen in previously. The playbooks focusing on revenue and customer growth/retention might fall short of finding the next big winners if the criteria is restricted to “having enough capital, a product that your customers love and an efficient sales machine”.

They might have to include “companies that can access AI infra, tightly control their AI supply chain and closely monitor their cost base and efficiency in an iterative way as they scale.”

AI is moving fast and we need to update our playbooks to keep up with it, probably giving a higher weight to the other side of the equation than has been the case in the past.

Until next time,

The Atomic Investor