Venture shock

SVB's demise has been like a shock to the venture ecosystem, shaking things off dramatically. Both for better and for worse.

The venture capital ecosystem has had a fantastic run over the last two decades. As investing in young innovative businesses became an acceptable source of returns for institutional investors, billions were ploughed in over the years into the asset class. A few big home runs set the flywheel rolling for future successes. Newer technologies became cheaper and the innovation cycles became shorter. Institutional capital became increasingly available for venture leading to larger funds being raised, that invested even more into tech startups and did it on repeat.

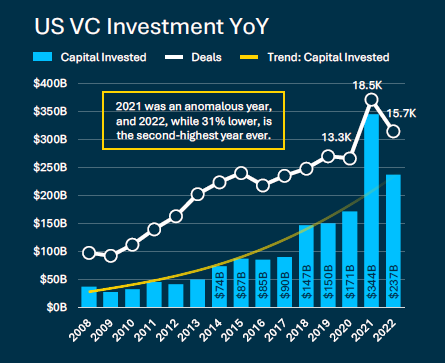

The U.S was early and more lax with regulation around investing in risky businesses, and with that the entire ecosystem flourished. VC funds in the U.S were already investing $30-40bn a year in startups around the time when the GFC hit. This increased by more than 3x ten years later in 2019.

But all good things come to end eventually. The downturn in tech and higher rates put the brakes on the venture train slowing it down considerably. From 2021 to 22, U.S VC investment was down 31% (from an insane and an abnormal year for venture in 2021) to $237bn (still the second highest year ever). But the demise of Silicon Valley Bank, the startup world’s financier and liquidity provider, was like a 440 volt shock to the system which seems to have brought that train to a screeching halt.

Not a whole lot of runway

According to some reports, more than half and close to two-thirds of all startups (and their investors) were using SVB’s products and services like deposits, loans, investment products, cash management, investment financing and more. It had almost become like the heart, pumping and recycling capital where it was needed, allowing young businesses to access credit and manage their cash operations and keeping the businesses alive. Now, the SVB shock has shaken things up in venture dramatically, both for better and for worse.

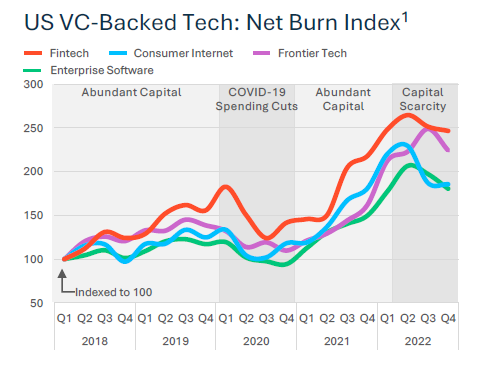

Tech companies in the last decade were high on the ‘growth’ potion. If they didn’t get close to those made-up fancy growth metrics that their investors wanted to see, they wouldn’t get the next cheque. In most cases, you had to pay more money to make more money and get to a higher valuation i.e burn cash incessantly on new hires, product, marketing, M&A, stock options - the whole package. It became a part of the venture DNA like an acquired trait. If you weren’t doing it something was wrong. And it made some sense given how low the cost of capital was. Growth was the only game in town.

But now when the tide has turned, the acquired trait is proving too hard to let go. According to the State of the Markets report by SVB (published just a few days before its collapse), the median net burn in U.S VC-backed Tech is up by 2.5x since Q1 2018.

40% of all pre-profit tech companies did reduce their cash burn in 2022 as VCs forceed them to take the profitability pill, but the share of companies that have less than 12 months of runway left went up considerably (and is still going up). This was before SVB went down. Now when VCs are pulling back and liquidity for risky businesses has been drying up, you can imagine things to have gotten a lot worse.

The balance of power is shifting

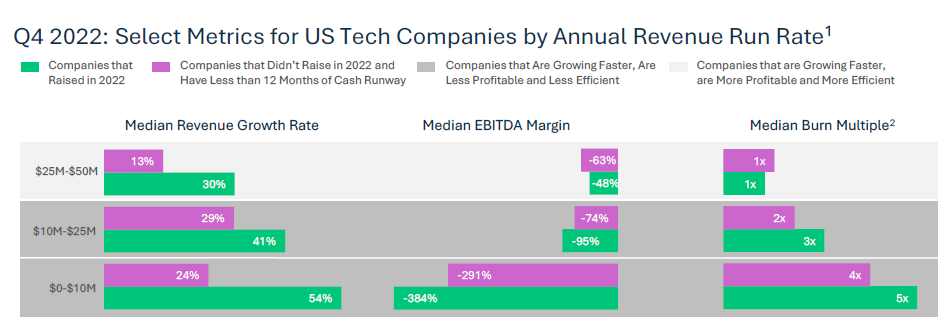

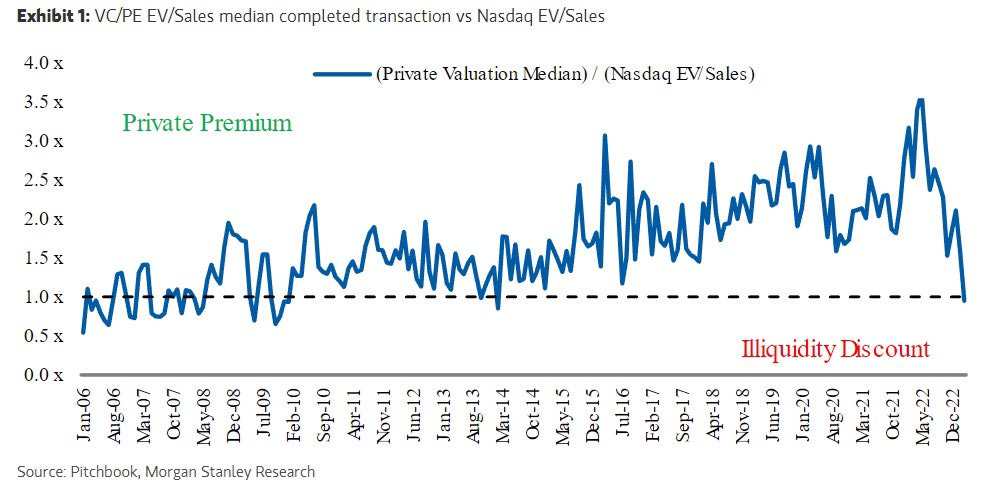

A sharp slowdown in the economy means lower consumer and enterprise demand, translating to revenue lower growth for tech startups. Combine that with higher risk-free rates and you get a multiple contraction leading to falling startup valuations (more like normalising) across sizes and stages.

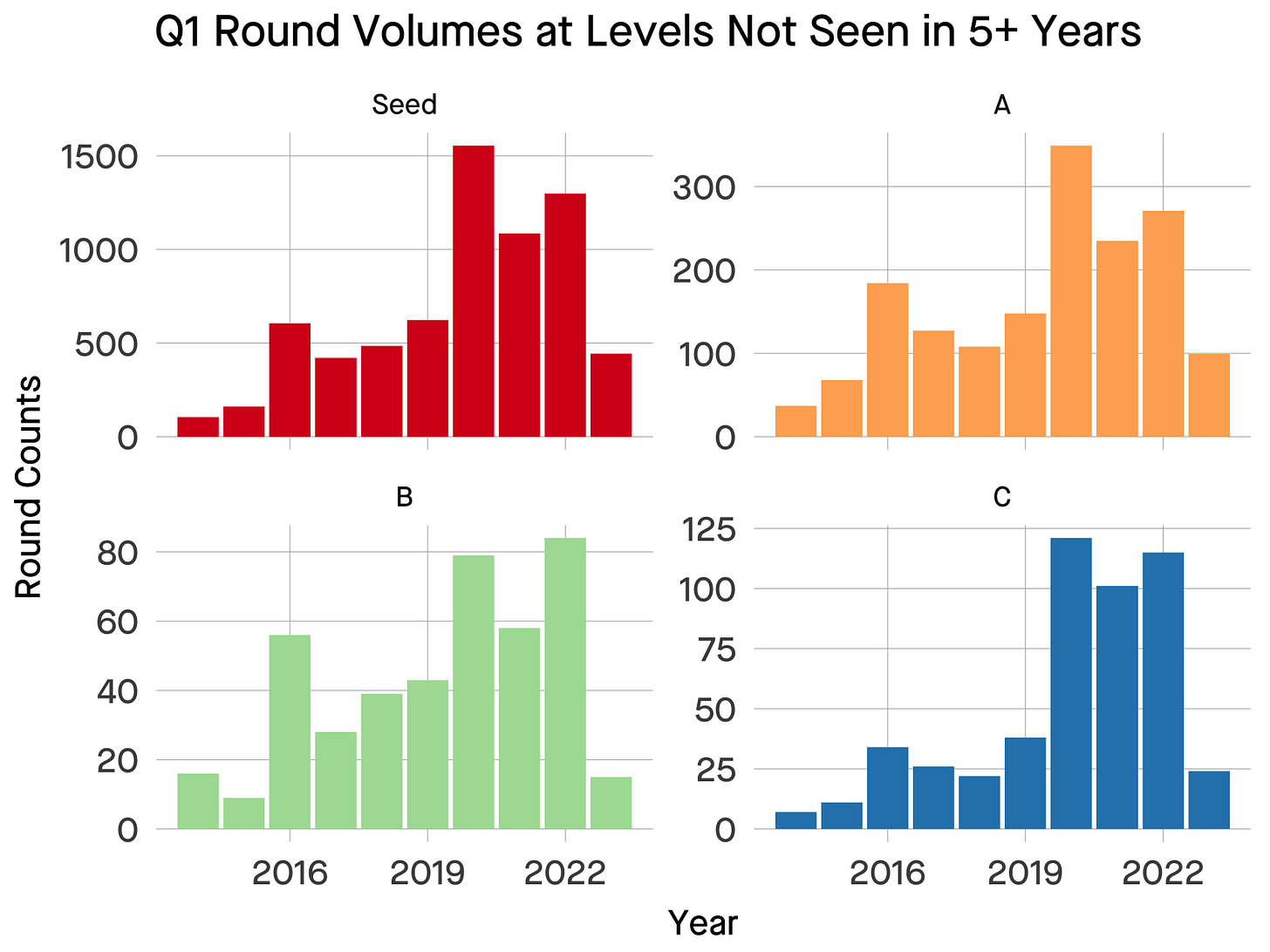

This might have started shifting the balance of power in the VC’s favour once again as capital becomes more scarce and hard to come by. It is getting hard to raise for startups, really.

Even the most successful tech companies are accepting massive down rounds. Stripe, for example, recently raised at almost 50% discount to its last valuation. Therefore it is very likely that smaller business would have to go through that pain as well just to extend their runway and survive.

Some startups will be worse off as they are forced to give up more of their company for much less and at terms that are not as favourable as they should have been. In the long-run, they might be better off as they are having to play by Darwinian rules. Only the fittest and the most efficient will survive which might benefit the whole ecosystem’s longevity.

Investing in VC might become attractive once more

Private markets, like their more volatile cousin, have been turbulent since Q4 of last year. With risk-free rates at 3-5%, fund managers’ hurdle rates are going up too especially in a high risk asset class such as venture. As rates climb higher, the percentage of funds that meet the minimum acceptable return level starts decreasing, as this chart shows.

Then, startup valuations are falling and catching up with public market tech multiples. Given that a large chunk of VC returns are still unrealised i.e based on valuations of the investments they’re holding, venture returns would have to ride the painful downward slide too. This is usually followed by an increasing gap between the top performing funds and the average funds, leading to higher allocations towards the top quartile or decile managers.

Best performing managers are more likely to outperform in an environment when they can invest at much cheaper valuations (except maybe in AI, a bubble in itself already). The opportunity set is narrower and fitter, consisting of startups with growth, PMF and realistic paths to profitability. On top of that, entry prices are cheaper which increases long term investment returns in itself. For VC investors and allocators, investing in the asset class might have become attractive once more.

This is far from over though. Till the venture ecosystem shakes off the shock from SVB’s fall, gets fitter and adapts to the new normal, we might not see the bottom in venture. But as things stand, it is much much closer than before.

Until next time,

The Atomic Investor