Understanding Private Market returns

PE and VC returns have outperformed public markets over long time horizons. The debate lingers on, but here are some interesting findings on how do they might be doing it.

Private markets’ ride to $13 trillion in Assets Under Management has been nothing shy of extraordinary. What started out as a niche asset management segment focused on leveraged buyouts of businesses back in the 70’s is a different beast today with ever expanding strategies and investment solutions for institutional and (very soon retail) portfolios.

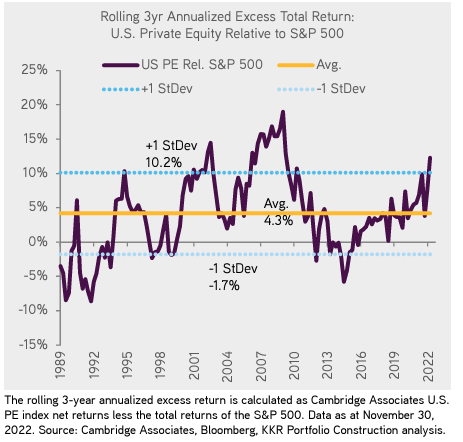

Different pools of capital, including pension funds, sovereign wealth funds, insurance companies and trusts have continued to increase private market allocations over the last two decades, chasing a steadier, diversified and less correlated return stream, which according to KKR, Hamilton Lane and various other sources has outperformed public markets over different economic cycles.

Private Market’s returns has become a contentious and a hotly debated issue over the last few years which is understandable as the investment universe becomes more barbell like - with passive stock and bond funds and ETFs at one end combined with private market allocations on the other. Active public market asset managers have lost considerable share to their private market counterparts, and it is not surprising to see managers and investors on this side of the debate to come out fighting and question private market returns.

Recent research on the topic uncovers meaningful insights to better understand private market returns and performance.

The sum is greater than the parts in PE

One rarely spends much time thinking about portfolio management when looking at PE. Dealmaking is the holy grail and each deal in a fund is scrutinised and revered before investing, during the holding period and after exit. GPs look at deals in isolation most of the time by gauging the return and value creation (alpha) potential for each investment opportunity.

But a recent paper by Gregory Brown, Celine Fei and David Robinson suggests that portfolio construction, including deal size and deal timing has outsized impact on fund level returns, more than individual idiosyncratic deals themselves.

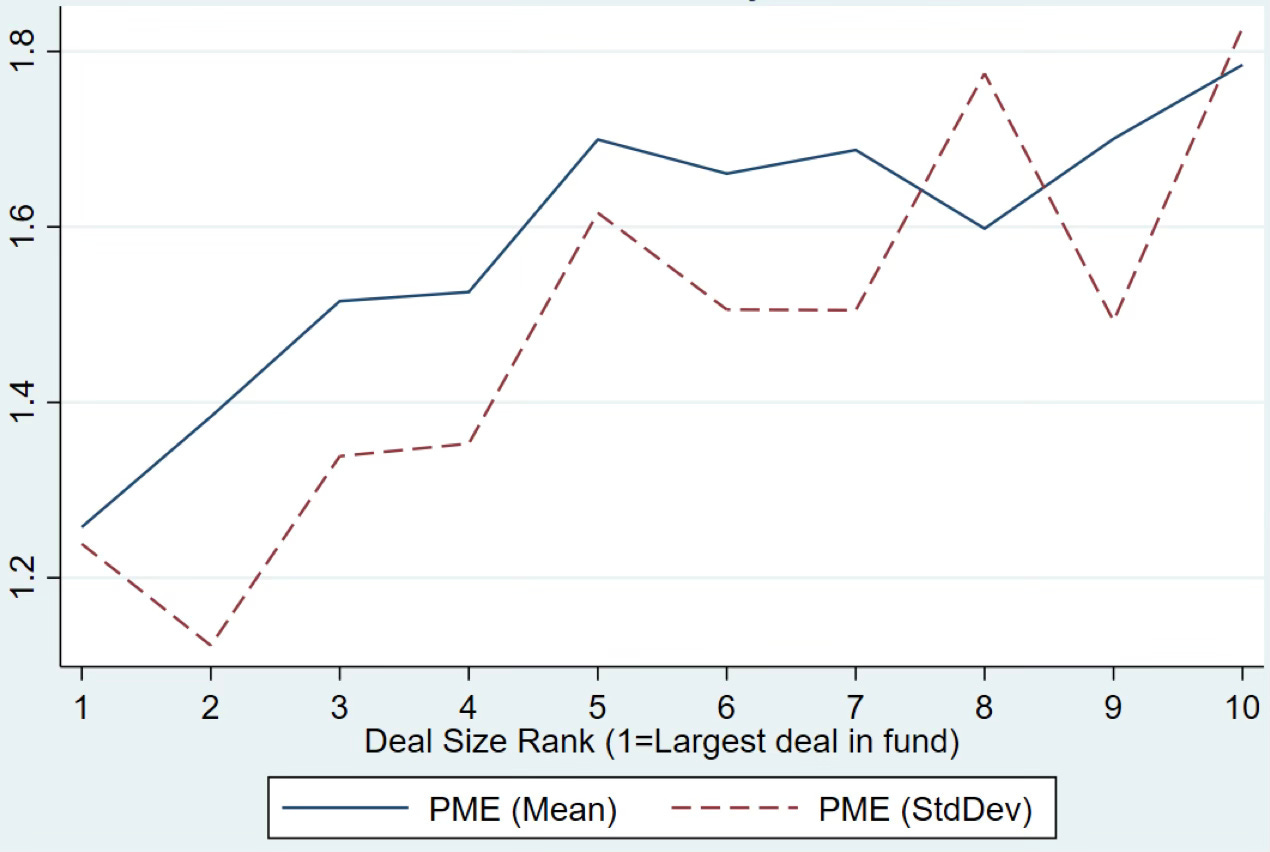

They looked at how GPs allocate capital inside a fund using a dataset of almost 6,000 portfolio companies for more than 450 buyout funds from 1999-2016 vintages. Ranking holdings from largest to smallest as a % of fund size, they found out that the largest allocations on average have the lowest returns, while the smaller allocations produce the best returns. Returns increase as they go from larger to smaller allocations. This comes across as counter-intuitive at first. Normally, fund managers would use position sizing to produce the best returns by allocating the most to their best ideas. But apparently not in private equity.

Going deeper, the researchers found out that average returns to average risk (or risk-adjusted return like the Sharpe ratio) was almost constant. GPs were essentially controlling for risk by betting more on less riskier (and lower returning) investments or betting the biggest on the “safest bets” rather than on the “best bets”.

The lower volatility that is part of the allure of private equity and is desired by institutional LPs is an important component of GPs’ portfolio construction strategy and therefore a driver for better risk adjusted returns as proclaimed by the PE firms.

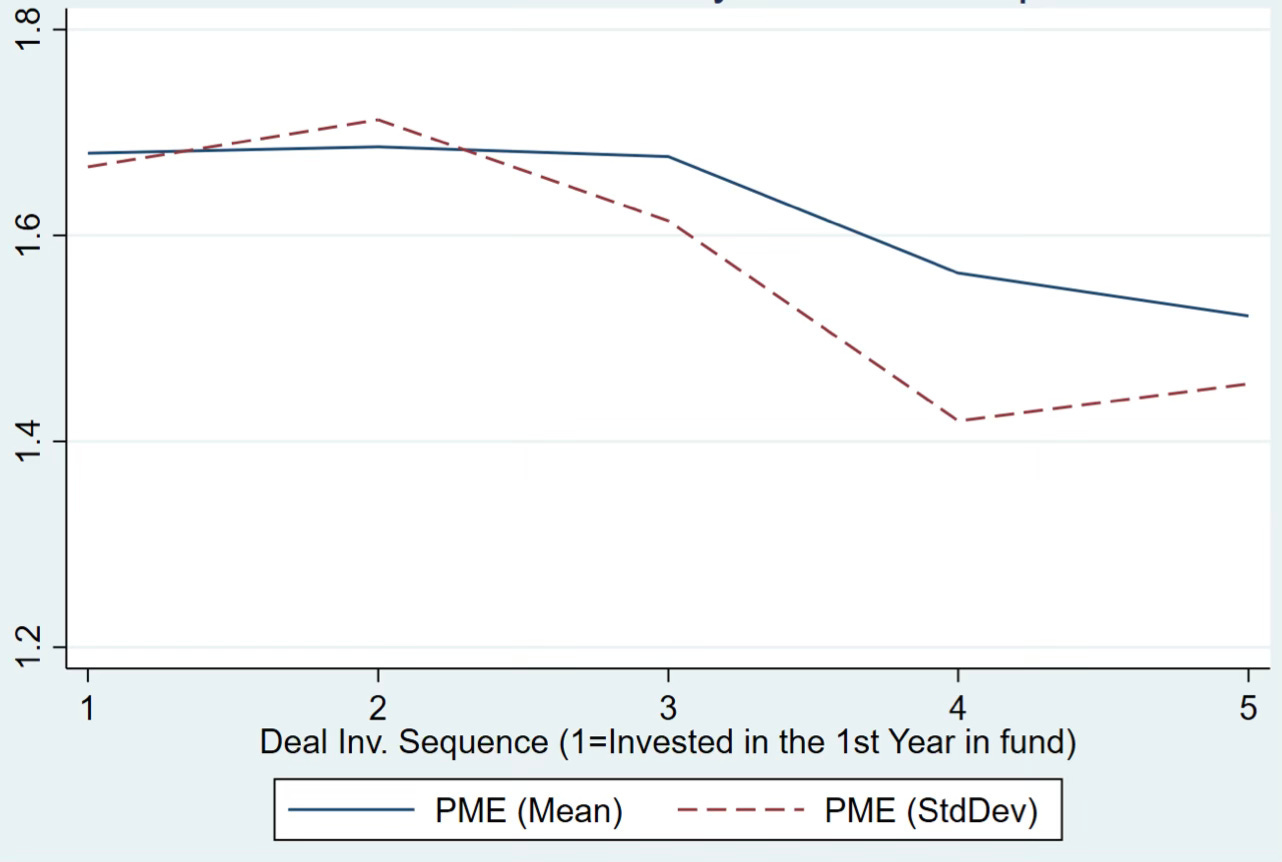

On timing of capital deployment, they found out that GPs deployed on higher return (and riskier) deals earlier in the fund’s investment lifecycle and moved on to the safer bets later, which might suggest kind of a hedging strategy to cap risk as the IRR clock is running its course.

The icing on the cake, however, was the return attribution to skill vs other factors. They discovered that at the fund level, 40% of overall variation between fund returns could be attributed to GP skill. The same number dropped to a meagre 4% at the individual deal return level (and was more than 90% to luck or other factors not in the GP’s control at the deal level).

This provides strong evidence of PE returns being driven largely by the GP skill in portfolio selection, construction and timing and not just by individual deal success. To put it simply, PE fund managers can have blockbuster deals that outweigh the rest of the fund but if they do not size their cheque and manage risk appropriately, it can the dampen performance of the fund significantly. This is hardly spoken about enough to give its due merit. Quite fascinating indeed.

Its all about the Power Law in VC

Venture Capital returns have a different profile. Empirical studies have found that there is high persistence in performance of VC managers. i.e success begets success.

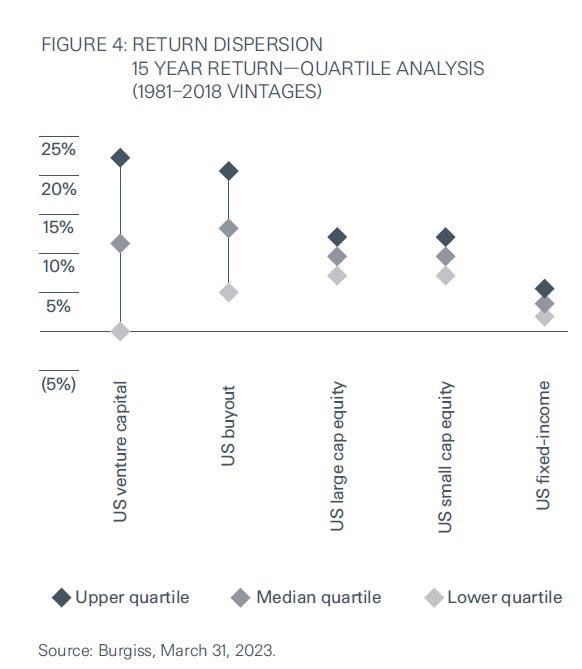

This has driven LPs to look at past performance as an indicator of future success in VC investing, and made manager selection an important factor contributing to the decision to invest. The performance dispersion in the top and bottom quartile funds is the highest in VC than any other asset class, which further increases the importance of the jockey (the manager) more than the horse (technology, sector, companies).

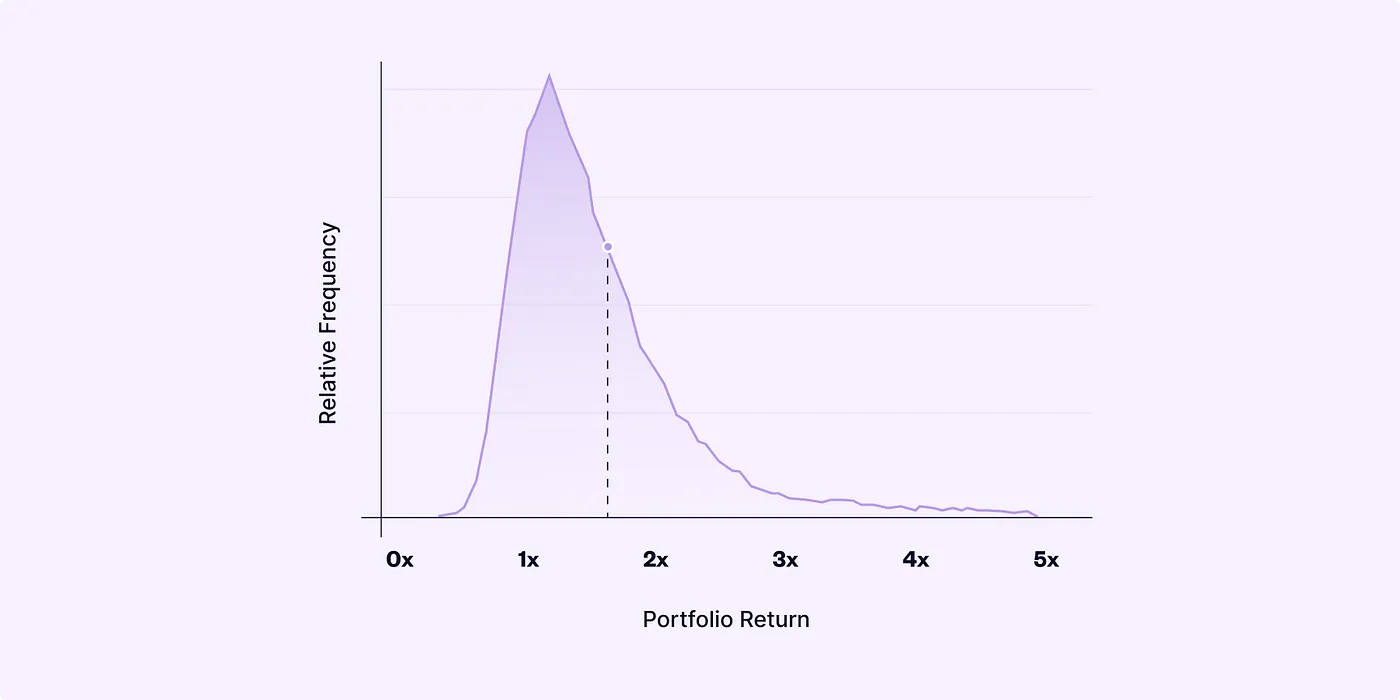

In addition, returns in VC follow an extreme power law distribution - the best bets are exponentially worth a lot more than the all the rest of the portfolio.

This suggests that they should constantly be looking for home runs and bet the house on them. But given high risk of failure (losing your money) in VC land, investors spread their bets across opportunities and increase their allocations as the company is de-risked, i.e matures and reaches the subsequent stages of its lifecycle.

How much of the “home runs” can be attributed to skill? There is not much empirical data on this but on the surface it seems like luck goes to play an outsized role on you hitting the exponential return goldmine.

Other studies have shown that asymmetrical information (knowing something about the about the company, industry or the technology that the average VC does not know) and the ability to win competitive deals differentiates fund managers from the rest of the pack.

Private Market outperformance is likely to continue being a contentious topic as the debate on the veracity of its returns lingers on. I tend to err on the side of caution and give merit where it might be due and caveat the hubris that comes with it at the same time. Private markets are increasingly becoming a larger proportion of institutional portfolios, which is likely to follow suit on the retail side as well.

Understanding the role they play in the portfolios and how they achieve what they do seems like a better use of time for all, be it public/private market managers, armchair experts, enthusiasts and the rest of the finance world.

Until next time,

The Atomic Investor